India may now find it even more difficult to retain Iran’s Chabahar port on its terms. The strongest backer of the Iranian port from India’s point of view was the Afghanistan government, which needed the facility and the associated railway line to its border town of Zahedan to import LPG, diesel, food and medicines. Those requirements still exist but the government there has melted away.

While India describes Chabahar port in its internal documents as the “Country’s first overseas port project with strategic objectives”, if it has to retain its immediate business viability, it will need the US government to continue with a waiver on sanctions against Iran. The waiver was given by the US to enable the erstwhile Ghani government in Kabul to obtain supplies on humanitarian grounds.

For those waivers to continue, India will have to recognise and deal with the Taliban government in Kabul. It will be odious for New Delhi as it will also have to accept that the Taliban government will hold the upper hand in the bargain. Finally, President Biden will have to agree that whatever has happened now in Kabul, the Taliban government still qualifies for the waiver. To put it another way, it is still a better customer than Iran.

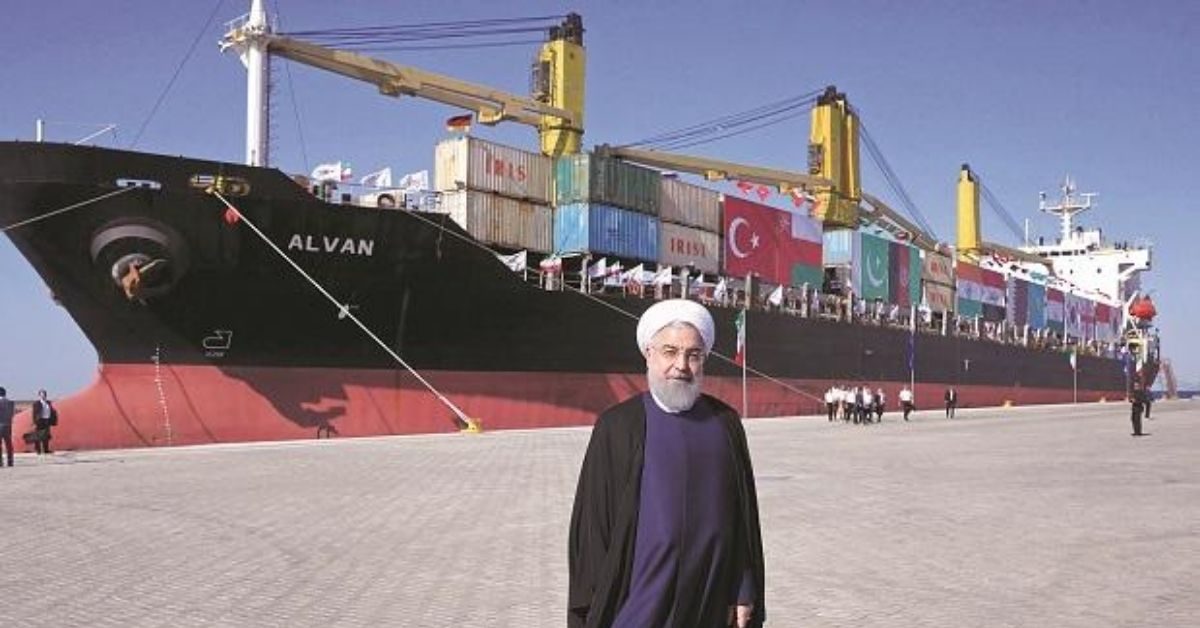

While the port has shipped about one million tonnes of cargo since 2018 when it became operational, future developments depend on this waiver. The Afghan connection is significant, which the India government recognises. “Chabahar port is part of our shared commitment towards peace, stability and prosperity of the people of Afghanistan. Chabahar has allowed India to export humanitarian supplies to Kabul and has also helped Afghanistan diversify its export opportunities,” a government document notes.

Although Chabahar is in Iran, the US had allowed three exceptions to the port from its sweeping sanctions on Iran. These were development of the port (by India), constructing a railway line from the port to Zahedan and the shipment of non-sanctioned goods from the port to Afghanistan. The agreement for the line was signed in 2016 during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Tehran in 2016. India’s Ircon and Iran’s CDTIC have yet to begin work on the project.

For India, the choices from here are not pleasant. The rail line is not going to be built to help the Taliban. If it eschews business with the Taliban, it will have to do business on Iran’s terms to develop the port instead, as the mouth of the proposed International North South Corridor.

Even if it does so, India could invite sanctions on all its companies that will invest in the two berths at the port– one multimodal and the other for container traffic. The US waiver is clear: “As Indian entities and partners proceed with the construction and development projects for Chabahar Port, it will be critical that any entities with which the Indian companies and entities engage do not have direct or indirect ties to IRGC (Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps).” It is akin to saying do not get involved with PLA-related outfits in China. Also, the waiver says any trade in metals or software with any Iranian company or the Iranian Central Bank is not acceptable.

It will involve considerable ingenuity on the part of Indian companies to try to tiptoe around these restrictions. None of them are also interested in doing so, since anything remotely suspected of connections can debar them from the global financial channels. This is the reason why the Indian government-run India Ports Global Ltd, which manages the Chabahar port as its sole business, has not been able to get rail-mounted quay cranes installed at the port for the past two years. The latest extended dates for receiving bids for the cranes expired today (August 18) and will be extended for the thirteenth time since February 10 this year. The problem has got compounded since the largest five manufacturers of these giant cranes, without which a container port is impossible to operate, are Chinese. While not explicit, India will not want its sole offshore port to be decorated with key Chinese equipment. The other two globally large manufacturers are German and Swedish companies.

The US waiver document notes that finished products (cranes do qualify) “intended for the construction projects at Chabahar port would not be considered (under sanctions), although even in such cases we would encourage due diligence to ensure no entities on the SDN list are involved in any related transactions”. The language is enough to scare away any European manufacturer. The berths, meanwhile, operate on makeshift cranes supplied by Iran.

Yet there are strategic risks for India to walk away from the proposed investment for the project, estimated at $85.21 million. It is certain that Iran will immediately court Chinese money. China is already building Gwadar port, in next-door Pakistan (196.5 km away). An Indian presence at Chabahar was a sort of checkmate that China will be happy to see disappear. Beijing has committed plans to invest $400 billion in Iran in several sectors including ports. Speaking at an India-hosted event, Raisina Dialogue this year, Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif said Chabahar port is neither meant as an offensive position to be used against the Chinese nor against Pakistan’s Gwadar port. Chabahar is just a day’s sea journey to Kandla on the Indian west coast.

Working with Iran despite all these risks means positioning Chabahar port to make it a part of the 12 nation INSTC project. External affairs minister S Jaishanker was part of the celebrations for a Chabahar Day at the Maritime India Summit in March this year to reinforce this objective. The 7,700 kilometre-long proposed route stretches from Northern Europe through Russia and Central Asia to Iran. From Chabahar port, it shall then be a sea voyage to Mumbai or Kandla. “I am hopeful that during the INSTC Coordination Council meeting, member states would agree to the expansion of the route to include the Chabahar Port and also agree on expanding the membership of this project,” the minister had said.

Sohel Kazani, Managing Director of Bharat Freight Group of Companies, has been involved with the Chabahar adventure for several years as a freight forwarder. He says there are enough reasons to merge the port with the INSTC project. Freight rates to Russia, by the Suez canal before the Covid-induced dislocation, averaged $650 a container, he said. “What tilted the scales in favour of a rail route was that time for travel was almost halved.” The current rates for a container to Russia (St Petersburg) from Mumbai is over $4,000.

A paper commissioned by the ministry of commerce had also pushed for this objective. INSTC’s business viability is hobbled by the current low volume of trade India does with Central Asia. In 2020, India’s trade with the entire region including Russia was just $16.1 billion ($15.8 billion in 2018), just two per cent of India’s total annual trade volume. Given such low numbers, it would be a considerable leap of faith for India to bypass the US sanctions and press ahead with Chabahar, with the immediate crutch of providing support to Afghanistan having also disappeared.

There is potential no doubt. Chabahar for instance could be a shipment port for gas from the fuel-rich CIS countries. Iran, however, has concerns since this would mean bypassing its own massive reserves. A long-running negotiation since 2014 to use low-grade Iranian gas for India’s Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers to set up an ammonia and urea plant near the port did not lead anywhere. Iran insisted that the negotiation should not be linked to concessions for the port, while India was keen to do so. As Kazani puts it, there is neither a market for the port, nor a builder available to build it.

It is a reflection of India’s ambivalence on Chabahar that even the dates for her involvement in the port are fluid. The contract for the two terminals at Shahid Beheshti port of Chabahar was signed in May, 2016 at Tehran between Aria Banader Iranian Port & Marine Services Company of Iran and India Ports Global Ltd. The contract was to run for ten years initially but once the US sanctions set, in it was difficult to decide on the 10-year time period. So the two countries agreed on a short lease contract instead, effective May 2018. It means India or Iran can cancel the deal, pretty much anytime.

India Ports Global Ltd is, meanwhile, scouting for a managing director. His role, as the advertisement puts it, will be to push INSTC “since Iran offers a gateway access to a large hinterland”. The candidate shall also explore opportunities to position Chabahar as a transhipment port for Middle East and Eastern Africa, it notes. For a company with an authorised capital of Rs 10 crore, these are ambitious objectives.

Source: Business Standard