China has ordered its two top coal regions to boost output and will allow coal-fired power utilities to charge customers higher prices as the country battles its worst power crunch in years.

Inner Mongolia and Shanxi told coal miners to lift combined annual production capacity by more than 160 million tonnes, while China’s cabinet said market coal-fired power prices may now fluctuate up to 20% from base rates, an increase on previous limits, or more for high energy consuming sectors.

The pricing adjustment is designed to prevent high energy consumption, state media reported, adding that prices for residential and agricultural users, as well as public welfare initiatives, would be kept stable.

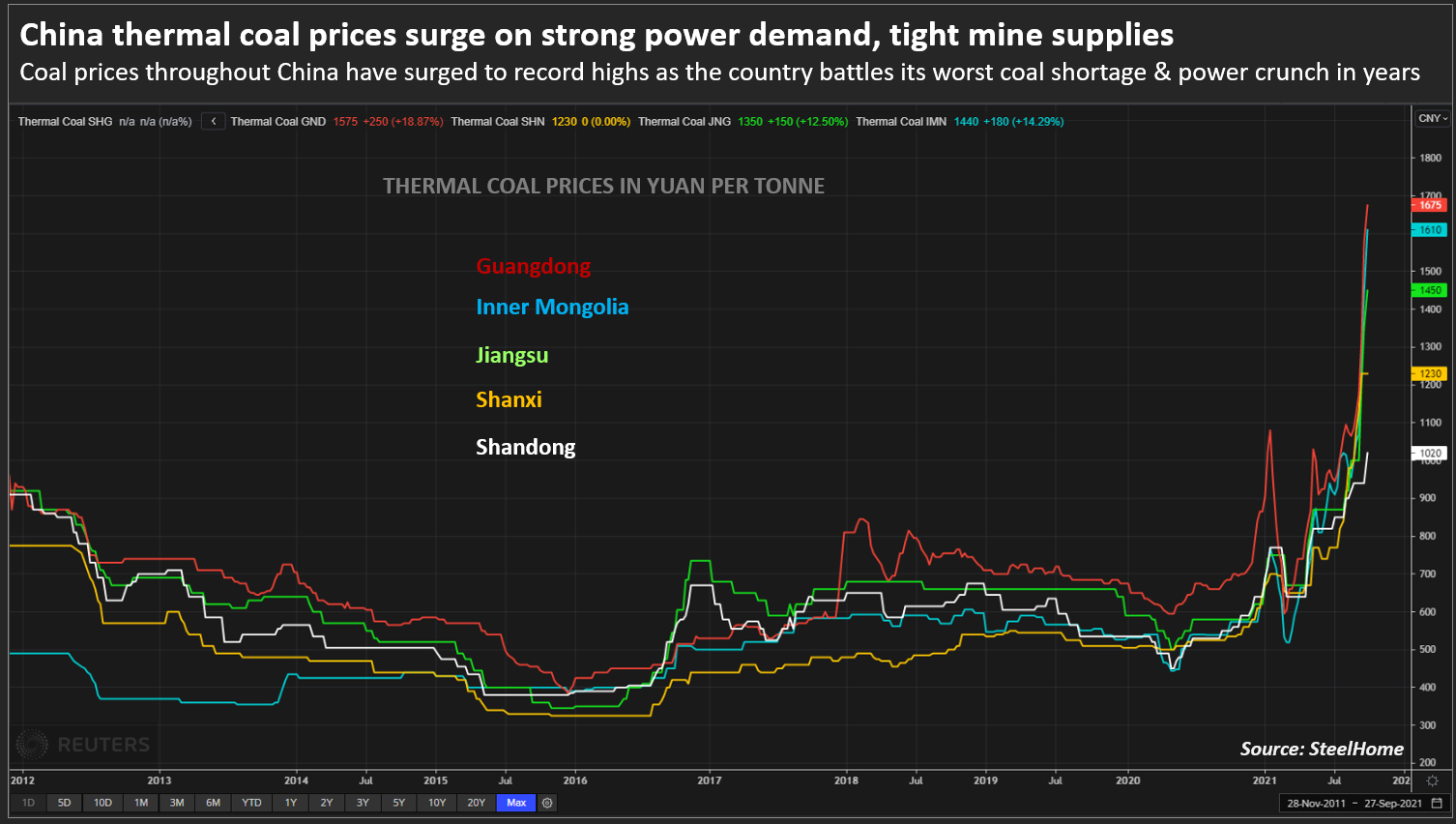

Near-record high thermal coal prices and electricity shortages that have prompted power rationing across China havedented the country’s industrial output and threaten its economic growth.

Shanxi, China’s biggest coal-producing region, ordered its 98 coal mines to raise annual output capacity by 55.3 million tonnes over the remainder of the year, an official from the provincial government confirmed on Friday in a document reviewed by Reuters.

Shanxi will also allow some 51 coal mines that had hit their maximum annual production levels to keep producing in the fourth quarter and to raise capacity by 8 million tonnes, which is expected to add 20.65 million tonnes of extra supply.

In China’s No. 2 coal region, Inner Mongolia, an urgent notice dated Oct. 7 from the region’s energy department asked local authorities to notify 72 mines that they may operate at stipulated higher capacities immediately, provided they ensure safe production.

A department official declined to say how long the production boost would last.

The notice followed a meeting whereregional authorities mapped out measures for winter energy supply in response to mandates from China’s cabinet, known as the State Council, the Inner Mongolia Daily reported on Friday.

“The (government’s) coal task force shall urge miners to raise output with no compromise, while the power task team shall have the generating firms guarantee meeting the winter electricity and heating demand,” the newspaper said.

“This demonstrates the government is serious about raising local coal production to ease the shortage,” said a Beijing-based trader, who estimated the production boost may take two to three months to materialise.

The 72 mines in Inner Mongolia, most of which are open pits, previously had authorised annual capacity of 178.45 million tonnes.

The notice proposed they increase that by 98.35 million tonnes, Reuters calculations showed.

“It will help alleviate the coal shortage but cannot eliminate the issue,” said Lara Dong, senior director with IHS Markit. “The government will still need to apply power rationing to ensure the balancing of the coal and power markets over the winter.”

China’s Zhengzhou thermal coal futures were trading up 2.2% at around 1,333 yuan ($207) a tonne as of 1347 GMT in Friday’s night session, not far off a record high of 1,408 yuan struck at the end of last month.

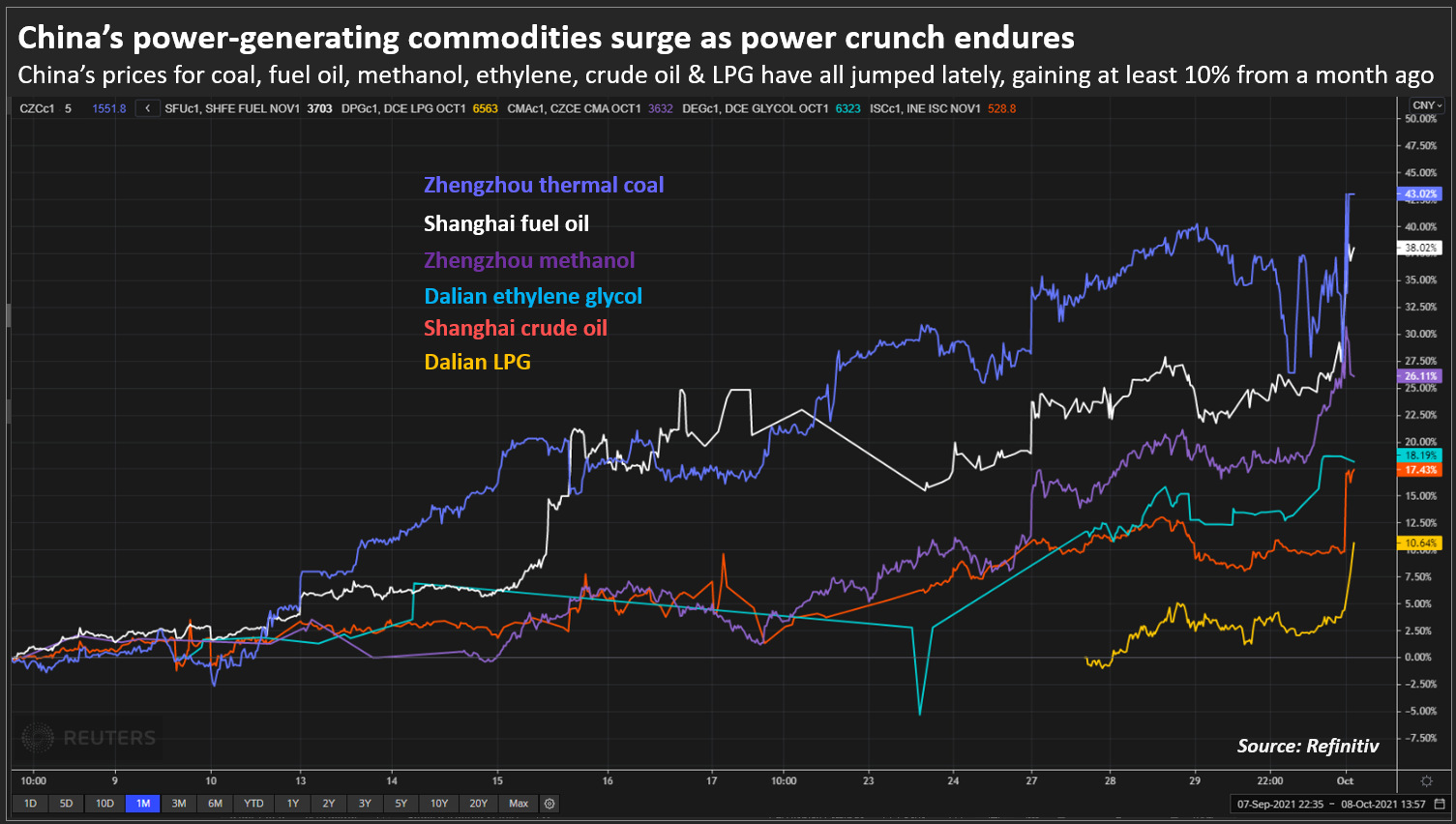

Prices of other power-generating commodities have also surged, including fuel oil , methanol and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) . All of which have gained at least 10% from a month ago as power generators scramble for fuel.

RAISING IMPORTS

Inner Mongolia churned out just over 1 billion tonnes in 2020 accounting for more than a quarter of the national total, official data shows.

However, that output was down 8% in 2020 and fell each month from April through July this year, partly due to an anti-corruption probe initiated last year by Beijing targeting the coal sector, which led to lower production as miners were banned from producing above approved capacity.

Neighbouring Shanxi province had to close 27 coal mines this week due to flooding.

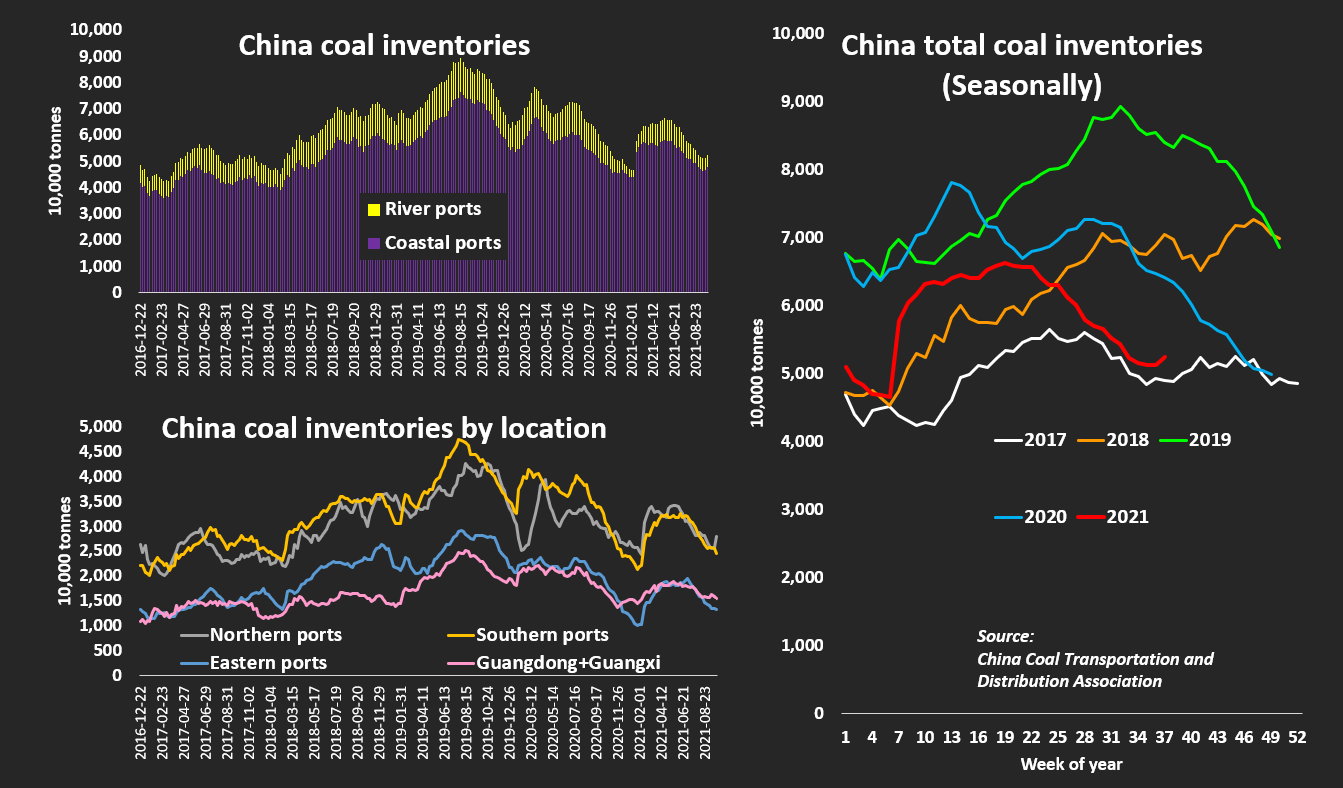

Coal inventories at major Chinese ports were at 52.34 million tonnes in late September before a week-long national holiday that started Oct 1, down 18% from a year earlier, data compiled by China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association showed.

To ensure power and heating supply to residential users, China has reopened dozens of other mines and approved several new ones.

The government has also called for “appropriately” raising coal imports to levels on par with last year, analysts said, after imports fell nearly 10% in the first eight months.

It has even released Australian coal from bonded storage despite a nearly year-long unofficial import ban, and utilities have tapped rare supply sources such as Kazakhstan and the United States.

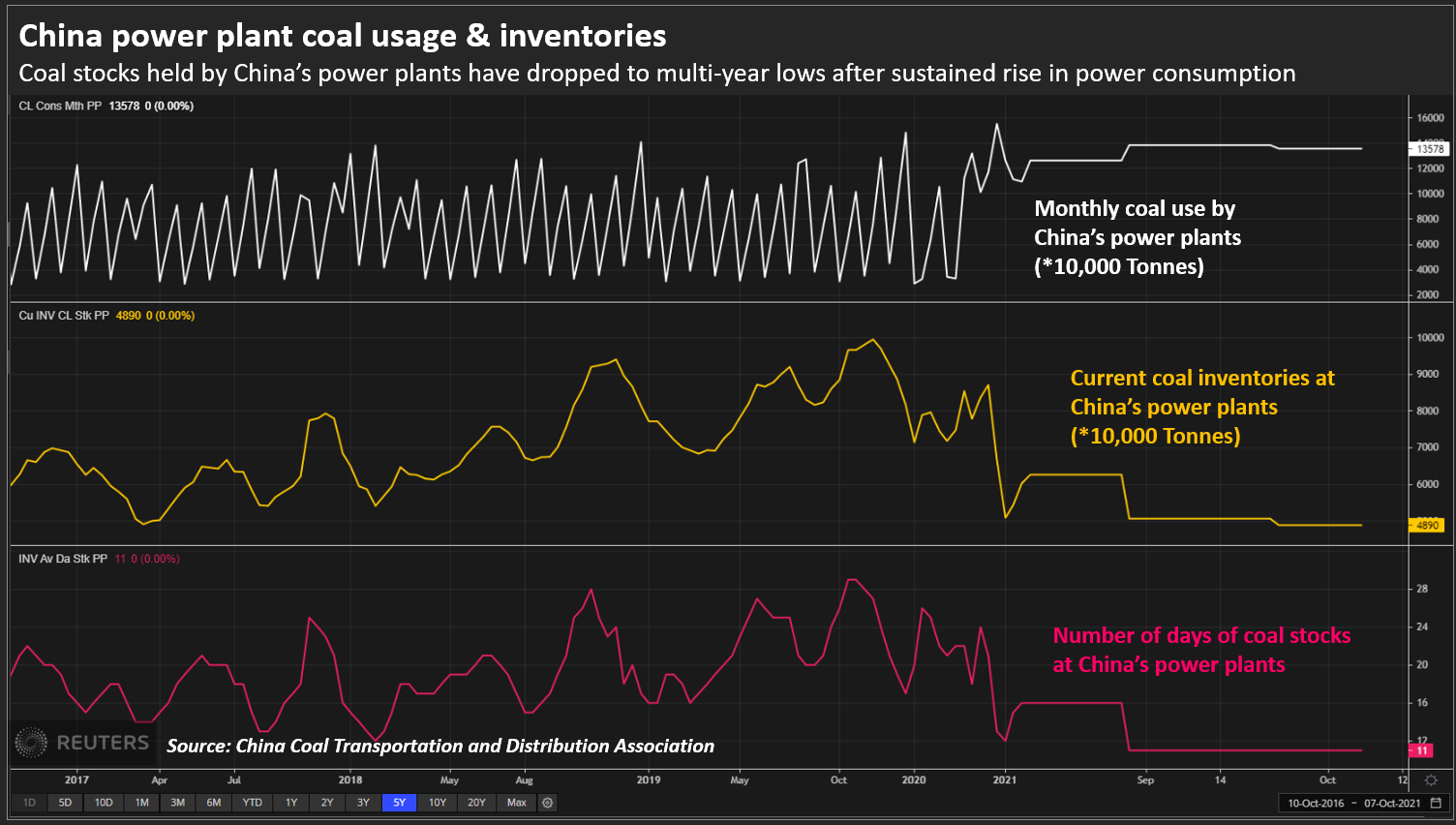

Meanwhile, coal consumption is climbing in northeastern China as the winter heating season has arrived, with major power plants holding average stockpiles of around 10 days’ use, down from more than 20 days last year.

ECONOMIC PRESSURE

Citi predicted that the squeeze would persist, forcing China to require a 12% cut in industrial power use in the fourth quarter – more in the event of a cold winter.

“This would increase stagflation risks and growth pressures on the Chinese and global economy over the coming winter,” Citi analysts wrote in a note.

Despite the announced output increase from Shanxi and Inner Mongolia, not much is expected to be added in time for this winter, analysts and traders said.

Analysts from Guosheng Securities expect China’s thermal coal shortage to top 116 million tonnes in 2021, despite some 31 million tonnes in newly approved capacity gradually coming on line from the fourth quarter.

“More (announcements to boost coal output) will be needed and we expect it to come,” said James Stevenson, coal analyst from consultancy IHS Markit, adding that China has used all its main tools to push domestic supply and manage demand.

Benchmark spot thermal coal prices in the northern port of Qinhuangdao hit a record high of 1,079 yuan a tonne in late September.

As coal prices rise, more power plants are seeing their balance sheets fall into the red and even face shutting down.

“Many more people and businesses would have been sitting in the dark had China just built coal power plants and not expanded solar and wind capacity,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

Source : Reuters