The global shortage of shipping containers has become one of the most hotly discussed issues in the shipping industry as 2020 draws to a close. There have been reports that exporters have not been able to ship their goods while carriers have been struggling to get containers where they need them. One shipping executive quipped on a media call that he would pay a reward if anyone could tell him where to find 20,000 boxes.

Despite the reports of disruptions and freight costs rising to record levels, the maritime research and analysis firm Drewry is out with a new report that says the problem is not a shortage of supply but rather a logistics problem. They suggest the problem is being driven not by underinvestment but repositioning issues, exacerbated in part by the carriers having blanked so many sailings in the first part of the year.

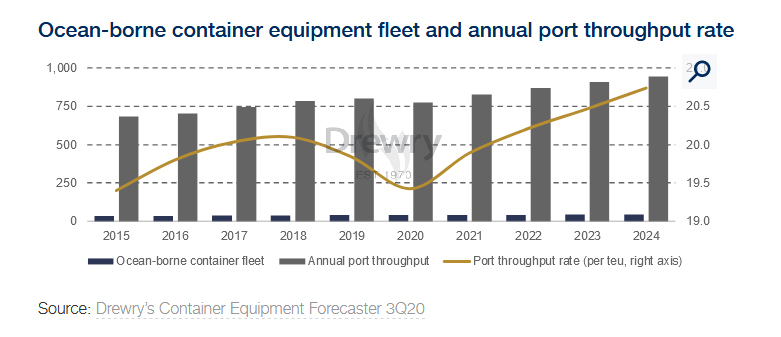

According to Drewry’s Container Equipment Forecaster, the global supply of ocean-borne containers is expected to have declined by just over one percent in 2020 to end the year at 39.9 million TEU. They compare that with a projected decline of over three percent in 2020 global container port handling. “This suggests,” Drewry writes, “that the former has more than kept pace with the latter.”

They acknowledge that the extent of the recovery in shipping throughput in the second half of the year took everyone by surprise, creating uneven levels of activity and how it impacted ports. They also point to this as the root of the current shortage. Drewry estimates that global container port throughput declined almost six percent in the first half of the year, while booming over 10 percent through the final six months of the year.

Despite this unexpected surge, Drewry highlights that the ratio of port throughput per shipping container, a key measure of equipment availability, only reached a reading of 20 in the second half of 2020. Their analysis shows that this is not particularly high by historical standards.

Drewry concludes, “This is indicative of a sufficient equipment fleet to support ongoing cargo demand.” Instead, they suggest that the disruption to container supply chains was wrought by the unprecedented number of blanked sailings, which reached as high as 30 percent of sailings on some trade routes in the second quarter of 2020. “That led to the current shortage of empty containers in key cargo demand centers such as China.”

The surge in cargo demand, however, has boosted investment in new container equipment. From a 35 percent contraction in global output in the first quarter of 2020, manufacturing has since recovered and is expected to reach 2.67 million TEU by the end of the year, according to Drewry’s Container Equipment Forecaster. They do acknowledge that it is down five percent versus 2019.

The demand for new containers is also contributing to strong increases in prices for the boxes. Starting at approximately $2,100 per 20 foot dry box in early July, the price reached $2,500 by the end of September. Prices were being quoted as high as $2,650 per 20 foot standard dry freight container in October, Drewry writes.

With demand for new containers remaining strong, and factories reporting full orderbooks into the first quarter of 2021, Drewry forecasts that output in 2021 will leap as much as 40 percent, with further growth anticipated in subsequent years. With manufacturing capacity fully utilized, they also say that further price increases are expected.

“The ramp-up of newbuild production will certainly help alleviate some of the ongoing container equipment shortages, but the greatest impact will come from a normalization of cargo demand development and carrier sailing schedules, as Covid-19 related disruption unwinds through the first half of 2021,” concludes Drewry.

Source: Maritime Executive