[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Apart from the locational advantage, being located on the East-West trade route, Sri Lanka is equipped with world-class infrastructure to seamlessly accommodate larger vessels across all three terminals, maintains a strong feeder system and is rid of congestion and other operational inefficiencies. For long, India has been at developing transshipment ports

As you drive past Colombo, Sri Lanka’s bustling metropolis, almost every inch of space is flattened for construction of new hotels or business towers. Yet, amidst all the industrious fervor, the corporeality of two things strikes you most. The majestic Buddha, standing tall granting his blessing of peace to everyone that goes to him, and the imposing structures at Port Colombo that welcome cargo to their shore from far and near before mighty ships carry them away to far off lands in their cricket-ground sized bellies.

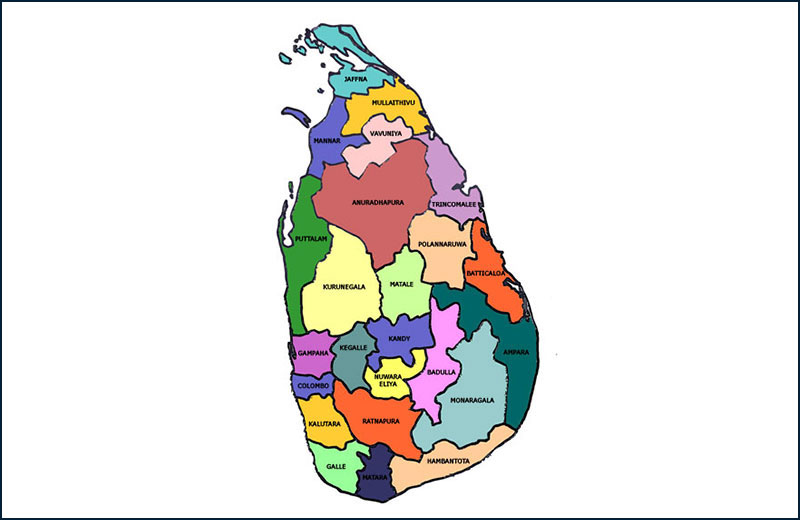

The reason why the shipping fraternity throngs at Colombo is simply because of where it is. Lying on the key East-West trade route and set close to India, Sri Lanka possesses the essential locational advantage needed for it to develop into a key logistics hub in South Asia. This makes the three terminals at Port Colombo – Jaya Container Terminal, South Asia Gateway Terminal and the Colombo International Container Terminal – the most sought after ones for all cargo that makes its way out of the Indian subcontinent to South Asia, Europe and the Americas. India currently depends on Colombo for much of its cargo to be shipped to the West because mainline vessels that can sail through deep seas visit the island country’s port for its world-class facilities in operating transshipment terminals.

While all of these three terminals depend mostly on India for their feed, a significant amount of cargo comes from Pakistan, the Middle East and Myanmar before being dispatched to Europe and South East Asia. And so, every year the cargo handled at Colombo is rising by 10 per cent despite the shipping industry waiting to recover fully from the impact of the global meltdown. Fifteen years ago, the throughput at Sri Lanka’s Colombo Port was a mere 500,000 teu and today; it is over 5 millon teu, which makes it the largest port in terms of volume handled in the Indian subcontinent. India’s Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust falls short a tad handling 4.8 million teu annually.

This math puts India in competition with Sri Lanka directly. For long, India has been at developing transshipment ports to wean away West-bound cargo to India and attract bigger vessels at its new-born ports in the southern tips of the country. The International Container Transshipment Terminal at Vallarpadam, Kochi was designed specifically for this purpose. But it failed to make a mark as shippers and shipping lines continued to sail toward Colombo for understandable reasons – some were commercial and others simply because it is praxis for the shipping lines to call there. However, Rohan Masakorala, CEO, Shipper’s Academy, Colombo says, “Geography is just one of the USPs of Port Colombo. Shipping lines continue to call India because every diversion to an Indian Port located even at the southern most point would require the vessels to travel anywhere between four and twenty four hours costing them an additional $25,000 to $50,000 per hour per vessel.” The other advantages that Rohan outlines is the sustainability in accommodating larger vessels across all three terminals, adequate infrastructure, a strong feeder system, lack of congestion. “Our customs compliance, border protection system, and universality of standards makes the terminals display a rating akin to other transshipment terminals such as Dubai or Singapore,” Rohan added. While 90 per cent of the cargo handled at Dubai and Singapore is transshipped to other countries, about 70 per cent of cargo that drifts in to Colombo is transshipment cargo. The rest accounts for textile, sea food, runner, tea industrial and agricultural exports from the country. What perhaps draws a lot of shippers to move their cargo to Europe and America via Colombo is because of the port’s strong feeder system. Smaller ships of 8,000-10,000 teu sail between Colombo to a host of maritime nations – East Africa, South Africa, Middle East, Far East and all South Asian nations – feedering cargo constantly. May be this explains why Colombo has been so successful in being a transshipment hub for 25 years now. Ted Muttiah, Chief Commercial Officer, South Asia Gateway Terminal says, “Big players will rationalise on more efficient hubs. Shipping lines cannot be doing a milk run along a string of ports if they want to rake in benefits from economies of scale.”

The rise of major shipping alliances and expansive vessel agreements has called for drastic measures in terms of achieving maximum cost and efficiency. While Sri Lanka has undoubtedly benefitted from investment and trade fuelled by China, it is sparsely populated country of just 7 million people. Yet, it has pipped India upping its ante on many fronts.

The CICT, established jointly by China Merchant Holdings and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority, boasts of a 50-feet draft with a 230-feet crane outreach catering to 14 services each week. This makes the terminal the big hitter among the three with SAGT and state-run Jaya Container Terminal taking turns in being the work horses and occasionally claiming the prized title of being the ‘terminal of the month.’ The 2M alliance between Maersk and MSC has worked in Colombo’s favour with the big boys of the shipping world marking Colombo as one of their pit stops while they pick and drop cargo from other parts of the world. In addition, Singapore’s PIL is the second largest terminal user at Colombo followed by the CKYHE and G6 alliances.

A senior executive at one of Sri Lanka’s infrastructure and maritime conglomerates who represented a shipping line for long said, “Shipping lines decide on which port will be the transshipment hub and not the other way round. And for any port to win the favour of the Triple E-Class ships, you have to make them an offer they cannot refuse.” Currently, these big size vessels that call Colombo enjoy a cost advantage over India’s ports aspiring to take after Colombo. The CICT terminal serves Tuticorin, Chennai, Kattupalli, Visakhapatnam, Kolkata, Haldia and Krishnapatnam on the east coast of India and Nhava Sheva, Pipavav, Cochin, Mangalore, Mundra and Kandla on the west coast, leaving out none. It is important to note here that cargo is carried from these ports in lightly loaded 10,000-teu ships as not all Indian ports can berth fully loaded vessels of this size.

“But if you cannot offer a comparative advantage, you have to offer a competitive advantage,” a former Sri Lankan government official heading a shipping business says when asked of India’s chances to be the next T Hub referring to Sri Lanka’s geographical advantage over India an unalienable one. Since the new government took over the reins in 2014, India, with its Sagarmala programme to string all its ports is actively looking at developing another transshipment terminal at Vizhinjam, Kerala, Colachel to compete with its island neighbor. This is because in the next 10 years, the Indian Ocean will become the new battlefield for China and India, which are jostling for control of the region. Maritime Security and trade are perhaps among the main determinants that would avow one nation’s might over the other.

For India to ace China, it needs to showcase its heft over the seas safeguarding military and trade interests. Keeping this in mind, India recently approved a slew of reforms to modernise the ports sector whose growth has been tardy being in the grip of the bureaucrats. “India’s problems do not lie within the port; they are outside of it,” Ted Muthiah says. And for anyone who has done business in India, this statement might seem familiar. Unfortunately, India’s railways and roadways that act as its lifeline are often congested with passenger vehicles making them gasp for breath when cargo movement is heavy. “For India to realise its dream of being a transshipment hub, it has to set in motion the dedicated freight corridors and private freight terminals,” a Former Secretary, Shipping of the Indian government told MG. Equally important is faster clearance by customs and lesser paperwork that would make doing business in India easy, he said.

With India currently finalising its plans to develop two ports in Kerala and Tamil Nadu to retain transshipment cargo, industry officials who work closely with both countries say India has to create a maritime ecosystem for all stakeholders in the industry to benefit from growing trade just like Sri Lanka is. “We are looking to create an atmosphere for expats, offer more options for financing and develop a sustainable bunkering facility and other marine services,” Rohan Masakorala said. Also, since it liberalised the port sector in 2000, Sri Lanka has seen very little unionisation and disruption from its workforce – two issues that continue to halt operations frequently at India’s biggest container ports at Chennai and JNPT. Its tariff structure is guided and has not changed dramatically since 1987 assuring constancy in business to its ports. Incidentally, tariff structure at Indian ports has been one of the most contentious issues with terminal operators calling for abolishing TAMP, or the Tariff Authority for Major Ports.

“Just as India is changing the rules of the game in other sectors, ports should be governed by an independent board with the entities functioning as corporate firms,” the former shipping line official quotes above said. Only this can arrest movement of cargo towards Sri Lanka.

In the financial year 2015, Colombo handled roughly 1.2 million teu of Indian transshipment cargo compared to 652,000 teu in 2014. Colombo garnered a major share of transshipment cargo accounting for 48 per cent of transshipped cargo from India, followed by Singapore, at 22 per cent, and Port Klang, at 10 per cent, according to data from the Ministry of Shipping.

One area where India perhaps squares off with Sri Lanka is the presence of a well organised logistics system. Although India is yet to come up with a sound logistics policy, the presence of large number of fairly sized domestic and international players has revolutionised the logistics segment. Sri Lanka too is emerging as a key sourcing base in South Asia for international buyers in the garment and plastic products sectors, leading to increased demand for 3PL services, including warehousing and transportation, as well as integrated supply chain solutions. Aside from Kerry Logistics and APL Logistics, there are a number of other foreign 3PL service suppliers operating in the island state, including Dubai-based GAC Logistics and Clarion Logistics. With the increasing flow of transshipment cargo through the island, Sri Lanka aims to further develop its logistics sector, providing integrated and high value-added services to international trading and transportation companies.

India’s aspirations to be a transshipment hub can soon be real. What is required in the interim is carefully described by SAGT’s Ted Muthiah – “For bigger ships to come, a port has to cut transit time because I think that is where the opportunity lies in filling them up. You need to incentivise the big ships; you need to broaden your cargo catchment area; you need to help them achieve the economies of scale. This will help them change their network. This is what Sri Lanka did. And this is precisely what India needs to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]